Numerical models: Crunching Numbers, Not Colours

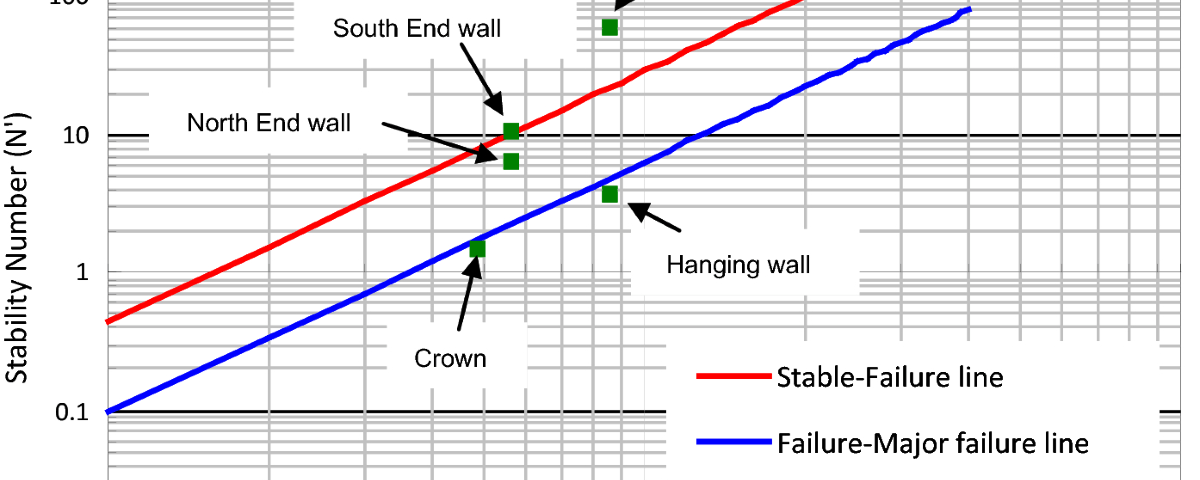

31 October, 2024In the pre-execution phase of a mine, site-specific observations of open stope stability are not available as reference cases for mine design. Therefore, the initial mine design parameters are based on observations of open stope stability and relations established from industry data (i.e. stability graphs). When a mine becomes operational, this aspect of design should be addressed. It is imperative that the Geotechnical Department’s personnel compile a site-specific database of stope stability observations to establish an operation-specific stability graph. Preferably, data should be gathered using instrumentation such as Cavity Monitoring Systems (CMS) to avoid bias or subjectivity due to human factors. The initial open-stope designs should then be validated using the operation-specific stability graphs as opposed to graphs that were established from data available in the industry.

There are various limitations that are inherent in the published stability graphs. This note serves to raise awareness of these and is based (in some cases verbatim) on the work by Suorineni (2010) who made a study of stability graphs. Some of the opinions expressed here are based on personal discussions with Professor John Hadjigeorgiou (on 30 November 2017).

Considerations for using Stability graphs.

- Reasonable caution should be exercised to ensure that the appropriate design charts are matched with the specific design requirements. E.g. Stability charts should not be used for entry methods such as cut and fill since the stability graphs were developed from data obtained from non-entry mining methods.

- On the Mawdesley graphs, the nomenclature ‘major failure’ and ‘caving’ should not be confused with rock mass behaviour observed in a block caving mining layout but rather be interpreted as ‘uncontrollable dilution’.

- The stability graphs should also be used with caution when applied to narrow vein orebodies (<=2m thick) because none of the earlier versions (Potvin, Nickson or Mawdesley) of the graphs considers orebody thickness in the definitions of the stability states. This becomes relevant when considering a stope hanging wall surface considered stable for an overbreak of 0.5 m in a massive orebody (at 10m wide), while ‘uncontrollable dilution’ is indicated for a 0.5 m overbreak in a 1m wide orebody. The databases used for the development of the original stability graphs exclude specifications in terms of orebody geometries, which were considered in the compilation of the original stability charts.

- A combination of empirical design methods is also recommended to validate the ranges of design parameters that are obtained from a single empirical design chart. Engineering judgement should be applied when using and interpreting the results obtained from stability graphs. Selecting the smallest stable hydraulic radius would not likely be the most economical business case and caution should be exercised in pushing the envelope for larger hydraulic radii in stope design. A good starting point for stability graph-based designs would be to determine a mean (weighted) hydraulic radius for an entire domain followed by refinement using geotechnical domains. When geotechnical data are available across an orebody, it is required to use geotechnical domains to express the variability in stable spans.

- As with any empirically based design method, the reliability of the stability graph method is largely dependent on the size, quality of data (observations) and consistency in the calculation of N’ in a specific database. The Mawdesley graph was based on 400 cases studies from Australia and Canada. The dilution-based method was based on 226 cases from Australia. It has been acknowledged that the confidence in the databases need to be improved by the addition of additional cases such as from Southern African mines.

- In most of the original stability graphs, the extent of overbreak (as an indicator of instability) were based on visual observation as opposed to cavity monitoring systems (CMS), which are quantitative and objective. The stability data used for the compilation of the graphs were not validated by inspection of mine openings. An exception is the Suorineni dilution graphs (which are based on validated CMS data).

- Stability number adjustments that cater for factors such as stope stand-up time, blast-induced damage (which can result in overbreak of up to 1m in depth) and the influence of faults are not fully developed at present.

- The effect of faults close to the stope surface is not accounted for in the Q’ system. Discontinuities sub-parallel to the stope walls may increase sloughing and this is accounted for in N’.

- Time effects should be accounted for as stopes are designed to last from 1 to 6 months from the first blast to depletion but often take longer to deplete. Time effects may dictate the choice and timing of backfill. The stope lifetime are often exceeded due to delays in the mining cycle. Sloughing has been indicated to be time-dependent and may increase with time.

- The stability of backfill surfaces is not accounted when backfill forms a stope surface.

- Subjectivity exists in defining the stability graph zone boundary lines except for the Mawdesley and Dilution-based graphs, which are formulated on statistical grounds. As the purpose of the stability graph is to predict stability states of future stopes from past performance of stopes it is more realistic to describe stability states probabilistically to avoid subjectivity in the nomenclature used for describing stability.

- Due to subjectivity in the nomenclature used to describe states of stability due caution should be taken when comparing results between the stability graphs.

- There are no guidelines as to when one type of stability graph should be preferred over others.

Relevance to the design charts of Mawdesley et al and Suorineni

- The extended Mathews stability graph by Mawdesley, Trueman and Whiten (2001) is based on the uncalibrated stability graph factors A, B and C. The authors did not complete follow-up work to establish confidence and reliability in its application in design. These authors argue that there is no significant difference between the original stability graph factors and the uncalibrated factors they used, thereby stating their confidence in their method. Due diligence should be exercised when referring to the cave zone in Mawdesley, Trueman and Whiten (2001) Extended stability graph charts. These authors’ definitions of stability zones are different from those defined in the commonly used stability graph by Nickson (1992) and imply caving (progressive unraveling and vertical propagation) as in block caving. It is recognised that the database used by the Mawdesley stability graphs did not distinguish between narrow orebody (<2m thick) and massive orebodies. Nevertheless, the Mawdesley (2002) graphs will serve the purpose of a sanity check on the dilution-based design method to ensure that design parameters do not result in potentially excessive sloughing (according to the interpretation provide by Suorineni (2010) of the use of the Mawdesley (2002) stability graph classifications). As the Mawdesley graphs are based on probabilistic analyses, the confidence in the method is higher compared to the original graphs, which were defined from inspection of line fits to stability data.

- Dilution-based graphs (Papaioanou and Suorineni, 2016): The data was validated using CMS surveys, CAD-based software, mine plans and geotechnical parameters were calculated in a consistent manner, which improves the confidence in the method. The data used were obtained from 226 cases studies from Australian mines. The results are applicable to non-entry methods. The statistical fits are independent of the thickness of the orebody as the units are expressed as percentage dilution, which make the graphs applicable to the wide range of orebody widths.

References

Mawdesley, C A, Trueman, R and Whiten, W, 2001. Extending the Mathews stability graph for Open-stope design, Transactions of the Institutions of Mining and Metallurgy, Mining Technology, 110(1): A27–A39.

Suorineni, F. (2010). The stability graph after three decades in use: Experiences and the way forward. International Journal of Mining. Reclamation and Environment. 307-339. 10.1080/17480930.2010.501957.

Papaioanou, A. and Suorineni. F. 2016. Mining Technology Vol. 125, Iss. 2,2016

Potvin, Y and Hadjigeorgiou, J. 2001. Chapter 60. The stability graph method for open-stope design. SME Handbook. Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration (US)

Hadjigeorgiou, J. 2017. Personal discussions on 30 November.